By Gerhard Lang-Valchs.

Edward Loines Pemberton was, together with John Edward Gray, one of the pioneers of British philately. Both were renowned experts and contributed several critical articles in various philatelic reviews concerning stamp forgeries. Pemberton was the author of the first British stamp catalogue and co-author of the book Forged Stamps: How to Detect Them, both published in 1862, and he also collaborated in The Early Forged Stamp Detector. From 1864 he was the editor of The Stamp Collector’s Review and Monthly Advertiser. The catalogues and handbooks published by both of them sold well and further editions were published.

In 1864 the Belgian stamp dealer and librarian Jean-Baptiste Moens edited and boundtogether the first illustrated catalogue Les Timbres-Poste Illustrés, from issues which had been published on a monthly basis. The year before, Pemberton had discovered amongst these issues seven illustrations that were not taken from originals, but from forged stamps, obviously part of the private collection of the Belgian (Ref. 1). When he reported this fact in an article in The Stamp Collector’s Magazine, he did not imagine that some years later he would have been the object of the same critical comments concerning his illustrations of Spanish stamps presented in his own catalogue (Ref. 2).

None of the six illustrations of Spanish ‘classics’ between 1850 and 1855 depicted inhis handbook and catalogues are taken from genuine stamps. But things are even more complicated. They are all, as we will show, not hand-made copies taken from a forged sample, but are direct copies from the original stones. In four cases we are dealing with known and described forgeries! (Ref. 3).

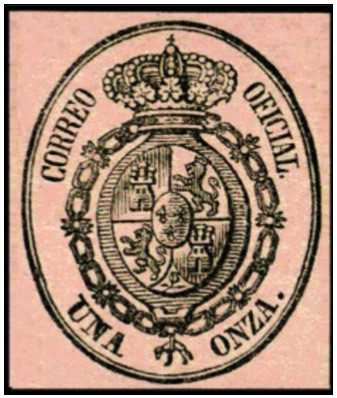

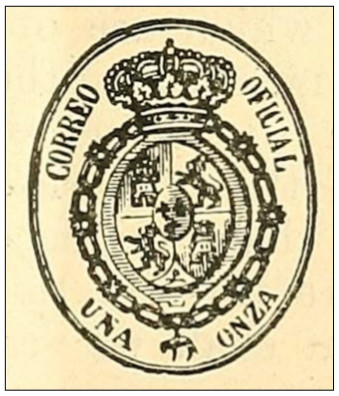

In order to prove the truth of our assertion, we will now present a detailed comparative analysis of two of those illustrations. As both show well-known and perfectly described forgeries, we will compare as a first step the original (Figure 1) with the illustration of the forgery (Figure 2) and then with the Pemberton illustration (Figure 3). We have to take into account that we are speaking about lithographs made at a time when photographic techniques had not yet been applied and used for forging stamps. So, for a good engraver the main problem was the accuracy of minute details, such as the correct number of background lines, circles of points or pearls, the number and location of shadowing lines. Nowadays, it seems difficult to understand why, in those years, forgers also failed in other, often more basic things. There was no generally accessible information about the design of the stamps until the publication of the first catalogues (1862). But even they gave only very reduced descriptions of the stamps and their design. Until the 1870s there were no illustrated albums or catalogues, and the philatelic reviews used to publish only illustrations of the newly issued stamps. This explains why some of the early forgeries were really bad copies.

The forgery is described by Graus and can be identified by the following defects or peculiarities (Ref. 4).

1. There are no final dots after ‘OFICIAL’ and ‘ONZA’.

2. The tail of the lion in the upper right quarter of the Coat of Arms only reaches half-way up its back.

3. The number of pearls of the crown from left to right is 5/7/3/6/5 in the original and 6/7/2/6/6 in the others.

4. The number of small horizontal lines surrounding the central oval of the Coat of Arms is 43 (left) and 47 (right) in the original, and has been reduced to 43 on each side.

5. Between the semi-ovals surrounding the horizontal lines and the extreme upper and lower points of the central oval of the Coat of Arms we count 3 and 4 lines in the original, in the others two (upper part) and three (lower part).

6. The line separating the upper and lower quarters of the Coat of Arms points in the original between the lines number 22 and 23 at the left and between 25 and 26 at the right side of the original, in the other samples between number 21 and 22 (left) and 20 and 21 at the right.

7. In the original, the location of the inscriptions ‘CORREO’ and ‘OFICIAL’ is horizontally level at the bottom (the ‘C’ and ‘L’) but not at the top (the two ‘O’s). In the forgeries, both the top and bottom are level. The same applies for the final and initial letters of the lower inscription (‘UNA ONZA’).

8. The lamb hanging from the central link of the chain shows two characteristic white spots in the middle. Graus only refers in his handbook to the first two points we mentioned in order to identify the forgery, adding as an additional sign the fact that the links of the chain are but a black mass (of ink). We cannot accept the latter as a general sign. The sample he presents shows clear traces of an excess of ink. The double oval frame shows in its lower part the same phenomenon. A closer look at the Graus sample shows some little white spots on the links. The surplus ink invaded most but not all of the small white surfaces that should appear next to black ones.

The presence of the differences (1-2) between the original and the forgery described by the Graus handbook makes perfectly clear that the Pemberton illustration is an illustration of a forgery. We can confirm a complete match even in the fine details (3-8) so it is clear that it cannot be a hand-made copy of a forgery or a forged illustration, but an identical copy taken from the original stone of a forgery.

The first time this illustration appears in a philatelic publication is in 1863 (Ref. 5). Three months earlier, another illustration of a Spanish stamp that we also consider a copy of a forgery had appeared in the same review, but, as far as we could find out, it was never described or mentioned as such in any publication.

Pemberton would not have been the only one that the critics focused on, although he was the first who published a forgery illustration (the one analysed above), ironically enough in the context of an article about forgeries of the whole series of that stamp (Ref. 6). Edward Gray shows in his illustrated catalogues the same stamps we find in Pemberton’s handbook, adding a seventh one we can identify at first glance as a forgery or at least a copy of a forgery (Ref. 7). E.S. Gibbons and the whole editorial staff of the Stanley Gibbons catalogue would also have been affected (Ref. 8). So we take for our second analysis a sample from the Stanley Gibbons catalogue of 1878 not to be found in Gray or Pemberton.

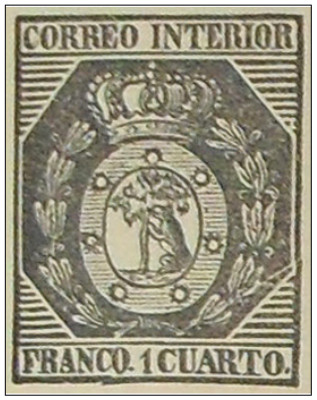

Analysis 2 – Figures 6, 7 and 8

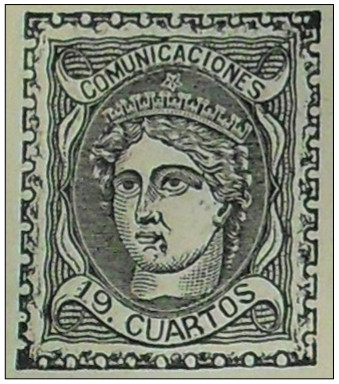

The description of the features of the forgery given by Graus is not really appropriate, but the comparison with the illustration shows clearly enough that we are looking at the same forgery in Figures 7 and 8. Let us see:

1. Upper inscription letters from left to right higher and narrower.

2. The two central pearls of the crown touch the lower and upper line.

3. The stars have no points.

4. The frame is broken at the lower right side.

5. The lower inscription is in bold lettering.

Numbers 1 and 3 are due, as we saw in our first analysis, to an excessive use of ink that does not allow distinction between the (strawberry-) tree (madroño) and the bear, number 5 is not really a objective fact and difficult to quantify. The other two features are all right. But in order to demonstrate once again that we are not only looking at a copy of a forgery but at an identical copy of the forgery, we will add some more details we find in both samples.

9. The horizontal lines total nine in each upper spandrel and only eight and seven in the lower ones, instead of nine in each on the genuine stamp.

10. There are only four instead of five lines between the lower part of the inner and outer oval.

11. The short horizontal lines between the outer and inner oval total 44 at the left and 39 at the right-hand side, whereas we count 35 and 30 in both forgery samples.

12. The location of the stars on those lines is identical in both forgery samples. (We will refrain from presenting the detailed comparative list of lines between the different stars and the lines the stars cover.)

13. The frame is not only broken at the right-hand side, but also at the bottom between the ‘C’ and ‘O’. There is a break line between the two points, originating from a break line on the original stone.

The second analysis reveals the same general results as the first. The Stanley Gibbons illustration is also a direct copy from a forgery, taken in this case from a forged and even damaged stone. It shows that even in more basic details such as the background lines of the spandrels forgers could fail.

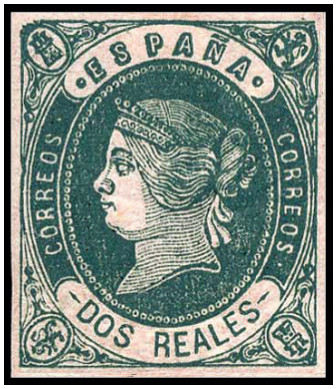

Until now we have focused our analysis on the very early Spanish issues and their illustrations. If we include the following years (1856–1874) in our comparison, we find more surprising results. Most of the later illustrations of the Spanish stamps are exactly the same in Gray’s and Pemberton’s publications; the same number, the same values, the same samples. And the Stanley Gibbons catalogue shows the same samples as well. Let us now analyse two of them.

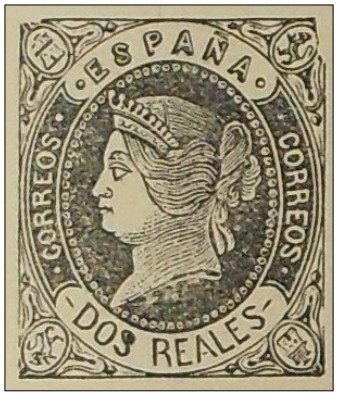

The two most eye-catching differences between the genuine and the illustration are the placement of the highest pearl of the queen’s diadem forming part of the ring of pearls surrounding the oval, and the peak of the bust that covers another one of the pearls or breaks into the ring of pearls. The number of pearls between the peak and the ‘diadem pearl’ (23) and the other (50) matches with the other illustrations. There is no shadowing of the nose, the dots enclosing ‘CORREOS’ are bigger than in the original, the lion’s tail no longer touches the back, and the differently styled ornaments of the lower part of the diadem are now continuous.

The illustration in this case is from a perforated stamp. The perforation used to be simulated by a kind of idealised frame, so that the stamps of the same series (with the same original perforation) with different designs made no attempt to represent the original. Those frames were part of the illustrations. So different copies of an original stamp used to have different frames. Not so in our case. We see the same (although sometimes damaged) frames with the astonishing number of 9, 10, 9 and 11 perforations at each side counted clockwise.

On the stamp illustrations the engraver’s signature (‘EJ’) does not appear below the bust. The mouth and nose show very distinctive strokes, easily detectable, but difficult to describe succinctly and properly. The ‘9’ of the inscription clearly differs from the original. The scroll below does not just touch with its lower part the frame but exceeds the wavy frame line.

The contrasting juxtaposition of original and illustration makes clear once again that the illustration in the catalogue was not copied from a genuine sample. Comparing the illustrations we cannot find significant differences between the samples of each pair, just as we could not in the previously analysed forgeries. Significantly we can only see small differences that can be ascribed to the peculiarities of lithographic copying and printing. So we have to conclude that these, as well as most of the other illustrations, are identical copies from the same stone.

A Europe-wide comparison of the catalogues of the 1870s shows that the phenomenon described is not limited to the British Isles; it occurs around the same time on the continent, too. About 50% of all illustrations of Spanish stamps in continental catalogues are the same, in some catalogues even up to 80%, and they represent the same value, which defies all rules of probability. And most of those repeated illustrations are, once more, identical copies taken from the original illustration’s stones, although, as far as I could see, they are only illustrations and were never used to produce forgeries. All this indicates that we have to assume that there exists only one common source of those illustrations, forgeries or not.

Going back in time, we observe that it was a British review that first published in 1863 one of those early ‘classic’ forgery illustrations (Ref. 9). When continental catalogues began to publish them, they had already appeared in the philatelic reviews and catalogues of the UK. So, should we conclude that they are the product of Pemberton, Gray or Gibbons or a forger associated with one of them?

It is not easy to trace the origins of the forgery illustrations that would lead directly to the forger. Let us summarise the facts:

– It concerns forgeries of early Spanish stamps from 1850 to 1855.

– We have no evidence that the whole series was forged, but only some values, and not necessarily the highest and most expensive ones.

– Nearly all illustrations found in the Torres catalogue are clearly detectable copies taken from the same original stones as the samples of Gray, Pemberton, and later Moens, Roussin and others.

– The later illustrations (1856-1874) were not used to produce forgeries.

– As far as the UK catalogues and reviews are concerned, there are no illustrations of other countries under suspicion apart from Spain.

Although the chronology points to a UK origin, there is and was no other evidence or suspicion that would implicate British philatelists in any action related to forgery or any transactions concerning forged stamps. The facts, when summarised, more likely point to Spanish authorship. The only Spanish candidate is Torres.

Why do we focus on Plácido Ramón de Torres?

– Torres was the only Spanish dealer of the 1870s and 1880s with international contacts and standing (Ref. 10).

– Nearly all the illustrations and forgery illustrations also appear in the stamp album of Torres (Ref. 11).

– Torres was a lithographer and he had made his own illustrations for his Italian review La Posta Mondiale.

– During his time in Italy he had designed what is called the Catania-bogus, proofs for a proposed issue of municipal revenue stamps for that city’s council. He had offered and sold them before they were officially approved (Ref. 12).

– He forged the municipal stamps of Leghorn in two versions and probably also the alleged correspondent proofs of the Livorno segnatasse.

As far we can see, we do not know any person outside the European network of publishers and stamp dealers who was interested mostly in Spanish stamps and able to produce and sell those Spanish copies and illustrations. Besides Torres, only the Senf Brothers and Moens were accused by some members of the philatelic community of strange commercial practices. Among others, Moens made reprints of the first issue of the stamps of the Spanish Carlist War, but he never offered or sold them as originals. The Senf Brothers of Leipzig included in their review sheets with facsimiles of stamps from all over the world. Although difficult to see, their reproductions were marked as such. Torres was, although not yet at this time, convicted by a German (1889) and an American tribunal (1892) for selling forged stamps. We have to admit that this was not for having forged those stamps, but for having sold them, knowing they were forgeries (Ref. 13).

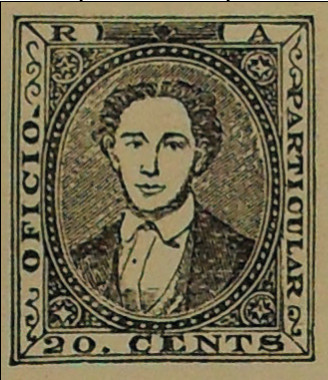

Further evidence for the authorship of the Spaniard comes from a curious stamp discovered in the British Isles. You cannot find it listed in any modern catalogue, not even in the catalogues of Cinderella stamps (Figure 14). It appeared for the first time in The Philatelic Journal within a conglomerate of stamps of different countries, without any indication of its origins (Ref. 14). Then it could be found again in the appendix of the Stanley Gibbons catalogue. We find it among other Spanish stamps, a fact that allows, apart from its inscription, its local identification, but it is not mentioned in the listing of the descriptive part of the catalogue (Ref. 15).

The stamp is not an official one, nor a revenue or municipal stamp of a Spanish city. It is not a stamp of any professional organisation either. If it ever has been the object of questions, those questions were never publicly asked and answered. The portrait does not show any nationally known person. It is not part of a political campaign as with the patriotic stamps of the last years of the century (Ref. 16). The stamp shows a self-portrait of Plácido Ramón de Torres. The fact seems most astonishing, until you take into account that, for example, Torres had published on his Italian catalogue’s front pages his own forgeries of the municipal revenue stamps of Leghorn, where he had resided, so that things take another slant (Ref. 17).

Apparently, it is the cryptic ‘RA’ of the upper inscription. It means Ramón Antonio. Those were the original two components of his name, inscribed in the baptismal register of his supposed birth-place Estepona, province of Málaga (Spain) (Ref. 18). He was a foundling and as such he had only one surname, de Torres, from his adoptive father, but not a second one, that of his mother, as Spaniards usually have. Changing the order of his names, Ramón Antonio Plácido to Plácido [Antonio] Ramón the latter could figure as surname, whereas the other two were only identifiable as forenames. So Torres could hide his dishonourable origins, much more important in those times than nowadays.

The combination of ‘OFICIO’ and ‘PARTICULAR’ does not correspond to any established term or expression in either ancient or modern Spanish. Never on any official or semi-official document, revenue or fee stamp, on paper or handstruck, is it known where such an inscription could be read. It is a kind of pun. Torres is playing with the collectors and the meaning of both words, something he often did with his illustrations. Oficio alone means “profession” or “official” (written) order; particular means, as in English, “special” or “personal”, alluding in a cryptic and sublime way to his very special task of producing illustrations and counterfeits.

How did the stamp get into the catalogue? We do not know. But we suppose that Torres told the editor that is was a sort of fee or revenue stamp. After years of supplying illustrations there was no longer any doubt about its authenticity.

References

1. The Stamp Collectors Magazine, May 1863, p. 27.

2. Edward Loines Pemberton: The Stamp Collector’s Handbook, Plymouth 1874. [Edifil [Ed] # 3, 6, 20, 29,

34, 36; Stanley-Gibbons [SG] # 4, 9, 25, 42, O47.

3. Francisco Graus Fontova [GR]: Manual de consulta de falsos de España, Vol. I-VII, Barcelona 1981-1987. The Ed/SG # 6 has not yet been described as a forgery in the philatelic literature. However, I have got a photograph of this forgery whose mere existence reveals it as a forgery.

4. GR, Handbook, 1855, 1 onza, Falso Filatélico (Philatelic Forgery) [FF] IV.

5. The Stamp Collector’s Review and Monthly Adviser, 1863, p. 36.

6. The Stamp-Collector’s Magazine, March 1866, p. 43-44.

7. John Edward Gray: The Illustrated Catalogue of Postage Stamps, London, 51870, 61875. The forgery of the 12 cts of 1852 is listed at the GR: Handbook as FF I and is easily detectable because of its curly hair ribbon. Most of the quoted editions of the catalogues are available and even downloadable at www.archive.org or play.google.com.

8. Gibbons ES, The Illustrated Catalogue of Postage Stamps, 1870 and The Imperial Postage Stamp Album and Catalogue.

9. The Stamp Collector’s Review, 3, 1863, p. 36 and 4, 1863, p. 55.

10. Plácido Ramón de Torres: Timbres-poste et fiscaux authentiques. Prix-courant pour marchands, Barcelona 1875.

11. Plácido Ramón de Torres: Álbum ilustrado para sellos de Correo, Barcelona 1879.

12. La Posta Mondiale, 4, p. 26-27, 32 and Gerhard Lang-Valchs [GLV]: “Il conte Giulio Cesare Bonasi accusato di frode”, Qui Filatelia, September 2016, p. 8-13.

13. Even if the tribunal had had proofs enough that Torres was the author of the sold and confiscated forgeries, they could not sentence him, because the illegal act of forging was committed in another country.

14. The Philatelic Journal, February 1875, p. 21.

15. Stanley, Gibbons, & Co.’s Priced Catalogue, 1879, Appendix, num. 1191.

16. Catalogue des timbres patriotiques d’Espagne. 1898. 1899-1901, Lyon 1964.

17. GLV: Il conte and GLV: “The Catania-bogus and the Livorno fakes”. [article to be published in Fakes, Forgeries, Experts 18.]

18. Archivo Municipal de Estepona, partida de bautismo no. 272 de 1847.

Editors note: Many of these 19th century publications are available in the Crawford library on theGlobal Philatelic Library web site www.globalphilateliclibrary.org.uk

This article was originally published on London Philatelist, April 2017, Nr 126, pages 132-138.