By Jerry A. Wells.

The 17th day of July, 1936 marked the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. The war lasted until March 28, 1939. The events leading up to the war are beyond the scope of this paper; but put simply, democracy and communism fought fascism and lost. A fascinating era of world history in great part due to the many famous personalities involved. 1/

The incumbent Spanish Government (Loyalists) was supported by Russia, as well as a large contingent of volunteers from over 30 countries (including the United States), forming the International Brigade. The units were generally inexperienced, understaffed, underfed, underclothed, under armed, and were composed of so many splintered groups that the element of an effective central command was woefully nonexistent.

The Loyalists were opposed by the Rebels, also known as the Nationalists or Insurgents, eventually led by General Francisco Franco but heavily supported by Germany (under Hitler) and Italy (under Mussolini). Italy provided about 100,000 troops, Germany about 6,000.

The European community, as well as the United States, resolved to, and did, enter a neutrality treaty to ban the providing of arms and ammunition to either side. However, neither Germany, Italy or Russia paid any attention.

During the Spanish Civil War the United States sent many naval ships into Spanish waters to accomplish a myriad of tasks including, but not limited to, the evacuation of American citizens, evacuation and relocation of American Embassy personnel, observance of military movements and strengths of various participating nations, networking with potential allies (particularly the British), and conducting our own battle practice maneuvers and naval tactics. 2/

Principally, two squadrons, the Spanish Service Squadron (A)-July 1936 to October 1936, and Squadron 40-T (B) – October 1936 through October 1939) operated off the Spanish shore during the Spanish Civil War. 3/ As originally developed by the Navy, each squadron was to be composed of two divisions of battleships, battle cruisers, or cruisers together with three divisions of other types of vessels. However, for the Spanish Civil War the squadron consisted of a light cruiser and two destroyers, plus various other ships temporarily deployed while on shakedown cruises. Of interest are ship covers from participating vessels bearing interesting caches and cancels.

I. SPANISH SERVICE SQUADRON. JULY 1936 – SEPTEMBER 1936

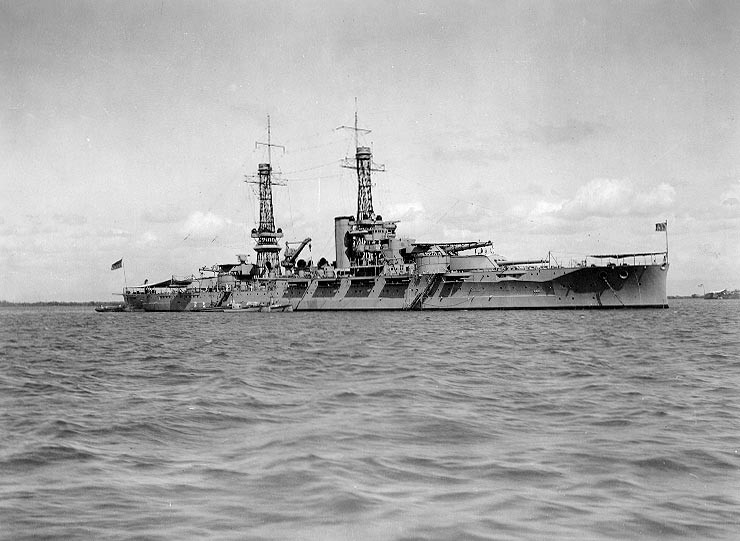

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July of 1936, the U.S.S. OKLAHOMA, the U.S.S. CAYUGA and the U.S.S. QUINCY (C)- were ordered to form the Spanish Service Squadron until they were replaced in late August and early September. Hereinafter all references to United States Naval ships will delete the term “U.S.S.”.

In July and August of 1936, the OKLAHOMA anchored off Santander, Bilbao and Barcelona to rescue refugees.

In July the QUINCY had just been commissioned and found her way on her shakedown cruise to Valencia , Marseilles, France , Barcelona , the Spanish Coast and Villefranche, France .

II. SQUADRON 40-T. SEPTEMBER 1936 – OCTOBER 1939

Information prepared by the National Archives and Records Service from publications of the General Records of the Department of the Navy and from the Operational Archives, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy describe Squadron 40-T as follows;

“This temporary squadron was organized and dispatched to Spanish Waters on September 18, 1936, in order to collect information on the Spanish Civil War and evacuate American citizens from war areas. The squadron operated out of Lisbon and Gibraltar until it was abolished October 22, 1940, by the Chief of Naval Operations.”

However, relief of the Spanish Service Squadron began in late August of 1936. Squadron 40-T was sometimes referred to as the “European Squadron”(D).

Upon the formation of Squadron 40-Tare, the RALEIGH became the flagship under commanding officer A.P. Fairfield (E). The original squadron consisted of the HATFIELD,KANE, and the RALEIGH . Later, these three ships were replaced by the MANLEY, CLAXTON and the OMAHA (F).

The Squadron Commander prepared weekly “Reports of Operations” (G)of fascinating interest to those interested in the role of United States vessels in pre-World War II as well as Spanish Civil War historians by providing insight as to the mission of those naval vessels in evacuating American citizens and embassy personnel in particular; gathering and disseminating information relating to military operations; International Brigades; blockade of ports by participants; relations with allies; ship damage; mining of ports and other areas; weather; relations with United States government and personnel; relations with foreign governments and personnel; International Blockade; U.S. ships operating in Spanish waters; foreign vessels participating off the Spanish coast during this engaging period; military operations including troop and supply movements. Beginning in June of 1938 the weekly reports became very sketchy and remained so throughout the remainder of the war; the reason is not clear.

Squadron 40-T and its support vessels utilized various French ports as their base of operations, mainly La Pallice , Marseilles St. Jean de Luz , and Villefranche , as well as Gibraltar . Excursions were made to Italian ports, mainly Genoa , Leghorn Naples, and Palermo ; to Ajaccio, Corsica ; to Lisbon ; to Algiers and Oran, Algeria; and to Casablanca and Tangier, Morocco. The main Spanish ports visited were Alicante, Barcelona, Bilbao , Cadiz, Malaga, Santander, and Valencia.

EVACUATION OF AMERICAN CITIZENS, EMBASSY PERSONNEL, ETC.

One of the main responsibilities of the Squadron was toaid in the evacuation American citizens, embassy personnel and foreign nationals. The first weekly report (October 31, 1936) of the Commander of Squadron 40-T stated that as of October 9, there was no evacuation of refugees from Spanish ports although ships of the squadron were ready to do so, and there was no information indicating emergency action. To the contrary, however, note that on July 25, 1936 the OKLAHOMA (H) aided refugees from Bilbao. However, evacuation of Embassy officials will probably take place, when it does occur, through Valencia rather than Alicante.

The first Squadron 40-T evacuation of personnel was mentioned in the October 31, 1936 report as “four American citizens and two Costa Ricans” from Barcelona. In the same report it was stated that there were 179 registered Americans in Barcelona alone. However, it should be noted that evacuation of personnel in Bilbao to St Jean de Luz on September 14, 1936 (I)and from Santander on October 8, 1936 (J) was conducted by the KANE.

In November of 1936, the RALEIGH evacuated twenty-four refugees, of which eighteen were America citizens, from Valencia and transported them to Marseilles, France. Additionally, it appears that 93 (including American consul and other refugees) were evacuated from Madrid on November 27 (K) and 28.

In December, the RALEIGH visited Valencia, were it picked up 27 person, 9 of whom were U.S. nationals. At Barcelona, the RALEIGH evacuated 10 additional persons.

In January, 1937, the safety of the KANE entering the harbor at Malaga precipitated a curt exchange between the Squadron Commander and the Chief of Naval Operations. Based on acquired information from the British Intelligence Office as to the safety of entering the harbor and that Italian, Spanish, French and British ships had already entered, the Squadron Commander then directed the Kane to enter the harbor. Prior to her arrival at Malaga, he was informed by priority despatch that the:

“practicality and assurance of safety for vessels entering Malaga was desired and that the State Department would then decide if KANE’s visit should be made; and that, pending receipt of this information, KANE should be directed to delay entrance to this port. At this point the Squadron Commander desires to point out to the Department that he had assured himself of the safety and practicability of entering Malaga before ordering KANE to proceed to that port, the Department’s original despatch of 1330 on the 12th having left this decision to the discretion of the Squadron Commander.”

More problems with Ambassador Bowers surfaced, in a February 1937 report that “Information received from Ambassador Bowers via the State Department to the effect that Santander is not mined and that Bilbao is swept and open to traffic has not been confirmed, and the contrary is believed to be true.”

The feud with Ambassador Bowers continued, centering on the evacuation of American citizens from Gijon in early September of 1937 when conferring with the Commanding Officer it was reported that Ambassador Bowers stated:

“he had recommended no more trips to Gijon be undertaken and had received an affirmative reply. In his opinion, this meant no more trips at all. Eleven Americans are known to be still is Asturias Province, 25 in Santander Province, and 47 in the vicinity of Oviedo.”

This report, reading between the lines, seems to perpetuate a distaste of the Squadron Commander for Ambassador Bowers, the latter of whom appeared less than anxious in taking any chances in evacuating American citizens. However, the Squadron Commander praised the efforts and cooperation of Paul Chapin Squire, American Consul at Nice.

In February of 1937 the KANE “* * * was directed to carry out State Department’s desire that consular officials be embarked at Marseilles and Gibraltar for purpose of investigating and reporting upon conditions in Malaga at earliest time considered safe for KANE to enter that port. British destroyers were also to commence investigation of those ports with the view of using them for embarking refugees.

In March of 1937, finding American diplomatic officials at Barcelona proved difficult, so the Squadron Commander requested all those with whom he might have occasion to communicate, to furnish the street addresses and telephone numbers of residences during non office hours.

At Valencia, the KANE embarked seven U.S. citizens and 3 from Chile, then sailed for Marseilles. The State Department considered it inadvisable to return any American citizens to Spain; but the Squadron Commander assumed that the prohibition did not apply to the American press; which presumption was confirmed by handwritten note in the report.

In May, 1937, the RALEIGH (L) rescued 155 Cubans from Alicante, Spain.

Also, in May of 1937, with the infighting in Barcelona between the Anarchists and the Loyalists, the British authorities sent two destroyers and the H.M.S. ARETHUSA for evacuation purposes, but were advised that the Anarchists held at least a portion of the docks and that during the height of the rioting, it was impracticable to evacuate refugees. A report that H.M.S. MAINE (British hospital ship) was docking at Marseilles with 49 refugees, possibly from Barcelona, was met with skepticism in the statement:

“It is obvious that in order to evacuate refugees, there must be a safe point of embarkation, a condition which doubtless would not exist while rioting and street fighting were in progress. No could Consular officials round up panic-stricken and generally helpless refugees scattered over a large area with shore transportation paralyzed.”

While mining at the Barcelona harbor was supposedly a problem, nevertheless the Squadron Commander felt the obligation to do everything possible to complete the evacuation:

With due consideration for the foregoing, the Squadron Commander * * * considered it practicable and advisable for RALEIGH to visit Barcelona, provided that Consul General Perkins stated that the evacuation of refugees was necessary and possible. (“Possible refers to a safe point of embarkation). While a certain measure of risk to ships of this Squadron exists, it is nevertheless small and should be accepted.”

Consular officials were embarked at St. Jean de Luz to arrive at Santander on the RALEIGH to evacuate additional persons. However, in early July, the KANE (not the RALEIGH) actually embarked Consular officials at St. Jean de Luz to arrive six miles off Santander to evacuate American citizens in rain and low visibility. Attempts were made by telegraph and radio broadcasts to round-up refugees scattered over a considerable area of surrounding country. Apparently successful, the KANE departed Santander with 68 American refugees, three Spanish and one English. Credit was given the Commander of the KANE for excellent ship handling, and arduous and efficient handling of boats and refugees, while hove to, during five days, six miles off the port of Santander.

A report issued by the American Consul described the evacuation procedures off the Santander coast. At first, the Governor would not give permission for anyone to leave. However, after personal appearances by the American Ambassador’s staff, refugees were embarked. All reasonable effort was made to evacuate all eligibles in the vicinity of Santander. It was not recommended that the ship again be sent to this locality, as most of those remaining did so at their own choice. Some additional evacuees were located and boarded. Many ships of different nationalities were present and active off Santander and “While at no time was there any apparent danger to the safety of the KANE, the possibility of sudden incidents with most serious consequences, cannot be overlooked.”

Plans were laid for the evacuation of United States citizens and 345 Cubans from Santander and Gijon, beginning 14 August of 1938. The KANE, with Consular officials on board, arrived at Santander on 15 August and embarked six Americans and seven Cubans, the great number of remaining Cubans had traveled to Gijon to board, but because of Government restriction for safety, the KANE returned to St. Jean de Luz without further embarkation. On 18 August the KANE departed St. Jean de Luz for Gijon but the acting Governor refused to allow embarkation of Americans, although other nationalities were boarded.

In late August the KANE again made preparations to evacuate American citizens from Gijon; the local Governor gave permission for the evacuation but the exercise proved difficult because of red tape of the local government. Apparently, the Governor’s reluctance was related to the “position of foreign governments in refusing to evacuate Spanish women and children while allowing the Insurgents to bomb them.” Secretary of State Hull cabled his concern over the length of time the KANE remained at Gijon in light of the reported

bombing of merchant ships in the area and directed the KANE leave with the least possible delay. About 25 Americans were embarked, as well as other nationalities.

All efforts to disembark 75 refugees on the KANE at St. Jean de Luz were refused, and the KANE was directed to Bayonne. Arriving at Bayonne the KANE debarked the refugees from Gijon. The Commanding Officer in conferring with Ambassador Bowers was chastised for apparently placing the KANE in harm’s way, which fact was controverted.

In November, 1937, when needing to accomplish embarkation of many women and children on the RALEIGH, the Squadron Commander was concerned with the potential problems in getting by local Spanish customs. It was determined that the Squadron Commander call upon the Spanish Governor of the Province of Valencia, who was a “well educated young lawyer, who was pleased and flattered by the visit and was very cordial in his greeting and manner.” It was apparent that the reason for the suggestion of the call was to “facilitate passage of the refugees through customs.

No other evacuation was mentioned in any later report of the Squadron Commander.

MILITARY OPERATIONS, INFORMATION GATHERING AND DISSEMINATION

The Squadron Commander’s weekly reports began with that of the week ending October 17, 1936. However, activity preceded the first weekly report, s.g. the only recorded attack on a United States ship was the August 30, 1936(M) bomb attack on the KANE off southwest Spain.

The weekly reports identified and tracked the naval movements of all foreign vessels during each reporting period. The military movements of all participants were traced through the use of first hand observation, reports of embassy personnel, evacuees, British and French naval vessels, local population and any other source available. The information contained was sifted for veracity with no holds barred in the reports. For example, in the very first report on October 17, 1936, the commander reported on the arrival of German pilots, Russian ships, and German steamships.

Insight into archaic World War I “gentleman’s conduct” between pilots proved to remain intact when the Rebels captured an American pilot fighting on behalf of the Loyalists, and the Loyalists had captured a Rebel pilot. The Commander reported in October 1936 that arrangements were underway for the American Consul, Seville, to take up informally with General Franco to effect an exchange (in order to save lives), both pilots to undertake not to fight for either side.

Apparently, while the Republican Flotilla Leader GRAVINA was in for repairs in Casablanca its only remaining officer deserted when command was seized by its crew and its elected committee placed in charge. (This was an interesting aspect of the Spanish Civil War, in that the Republicans were of socialistic bent, and under this applied theory no one was in command, the decisions were to be made by committee. The “headless command” syndrome of the Loyalist military machine was a contributing factor to the adverse outcome three years later.)

In December of 1936, the Senior Aviator of the RALEIGH passed by the airfield at Palma, requesting but being denied entrance, but noting the airfield being rapidly improved by several hundred workmen; the protective cover of anti-aircraft field guns; and

presence of 6 up-to-date pursuit planes and several large Italian Breda type bomber; two seaplanes of the Italian Macchi fighters; and reporting the presence of 200 Italian pilots.

Military and naval information was also being obtained from the local office of U.S. Ambassador or British Ambassador, neither of whom had reliable sources of information as compared with the British intelligence units at Gibraltar.

The Spanish Government ships and crew were the subject of derision by the Squadron Commander who reported in January of 1937 that these flotilla leaders have never been in action, one submarine firing two torpedoes at a merchant ship in Tarragona and both missed the ship but struck the breakwater.

In February of 1937 the Commander reported that the local dissensions among radical groups have resulted in some actual bloodshed within the city (of Barcelona). To a shortage of bread, gasoline, and other essentials, there is now added a serious shortage of coal, which is handicapping transportation service. There is a general disorganization so that conditions are growing worse instead of better.

KANE’S visit to Malaga in February, 1937, reported on the effects of the war which seemed to be minimal: “small percentage of buildings gutted”; “appearance of city was clean and in good order with everybody busy cleaning up.”; “Street car lines were running.”; “Food lines were orderly.”; “There was apparently sufficient cheap food with scarcity of meat, eggs, and vegetables.”; “No infectious or contagious diseases.”; “General Franco is anxious for all Governments to re-establish consulates as early as practicable.”; “General populace cheerful and more hopeful than in any Loyalist port visited.”; and reporting information received from British Intelligence Office, Gibraltar, the “Rebel forces engaged in the capture of Malaga consisted of a total of 20,000 men, of whom 6,000 were Italians.”

During the week of May 3 through May 7 of 1937 a serious revolt was reported to have taken place in Barcelona, with street fighting between the Loyalist government and the anarchists resulting in several hundred dead or wounded; the situation remains critical and confused with the outlook gloomy; evacuation of foreigners impractical. On May 9, the Squadron Commander reported that it is difficult to take any other than a pessimistic view of future conditions at Barcelona.

In the summer of 1937 the Rebel General Mola and four officers were killed when the plane in which they were flying struck a mountain during foggy weather. This event proved of extreme importance to the career of General Franco by removing any impediment to his rise as the undisputed leader of the Nationalists.

In September of 1937 the Commander of the KANE reported that Loyalist ships were attempting disguise by being fitted with slides so that they can slip in plates in stern and bow to change their name after leaving port, and have been painted in colors to be confused with British ships. In that same month the RALEIGH (N)reported “passing through a mystery sub area”, but the “mystery” was never later resolved.

In late October and early November of 1937, the HATFIELD and the KANE completed their duty with Squadron 40-T and sailed for home and were relieved by the MANLEY and the CLAXTON.

On December 4, Admiral A.P. Fairfield, Squadron Commander of Squadron 40-T, was relieved by Rear Admiral Henry E. Lackey (O).

In February, 1938, the Commander reported that Barcelona was bombed by the Nationalists using a new explosive of a force hitherto unknown and that compared to them the bombs used in World War I seemed like toys – whole blocks were said to collapse with the explosion of a single bomb. Apparently, one of the first uses of the so called “blockbuster” bomb. The British expressed their horror at the belligerent’s tactics of bombing civilian targets, and appeals were made to both the Loyalists and Nationalists. Signatories included the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Hinsley, Chief Rabbi Dr. Hertz, Lord Mayor of London, Lord Chief Justice Lord Howard and other leading financiers, artists, sportsmen, scientists and economists. Strangely, no British politician signed the appeal.

Radio press reported on February 19 that:

“General Franco, refused today to accept a British proposal for a ban on the bombing of unfortified cities by airplanes fighting in the civil war. Franco said he appreciated the humane purpose of the British proposal but was unable to give a promise to end bombings. The Rebel General expressed regret over the loss of life caused by Rebel air raids.”

The OMAHA (P)set sail in February 1938 to join Squadron 40-T.

The RALEIGH sailed for home from Villefranche in late April enroute to Norfolk in May of 1938, arriving in Norfolk, Virginia.

INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES

In May of 1937 the Squadron Commander reported that twenty-five Americans were arrested some time ago for trying to enter Spain, and their passports were held by the Consul. The men were released with orders to leave the country within two weeks and:

“Where they are now, no one knows. Reliable information emanating from our consul at Le Havre is that some 800 Americans arrived at that port about the same time as the 25 arrested.”

On or about June 1 the Spanish Merchant Ship CIUDAD DE BARCELONA was sunk having on board 1000 volunteers destined for the International Column most of whom were lost. Included in this number were 104 Americans of whom over 50 were lost. Additionally, the ship was laden with war materials including 800 airplane engines of American manufacture.

In July, 1937, heavy fighting occurred in the Brunete sector, west of Madrid, with the Rebel forces retaking most of the ground previously won by the Loyalists with the effort of the International Brigade.

In September of 1937, in the French harbor of Brest, 12 men dressed in civilian clothes attempted to seize the Spanish Loyalist Submarine C-2, led by the Nationalist Military Governor of Irun. One of the boarding party was killed and six arrested. Instrumental in thwarting the attempted seizure were the Captain and crew of the Spanish Loyalist Submarine C-4, at Brest for repairs.

In October, Press despatches from Salamanca stated that American Airman Harold Dahl and three Russian airmen were sentenced to death by courts-martial; but were instantly reprieved by General Franco. (As an aside, Mr. Dahl’s wife was a beautiful show girl, and successfully appealed to Franco for his personal intervention for the safety of her husband.)

Information received from reliable sources reported that the total number of Italian and German volunteers entering Spain were 81,000 and 9,000, respectively.

Subsequent to November of 1937, no additional reports on the International Brigades were made by the Squadron Commander.

RELATIONS WITH LOCAL AUTHORITIES

In December of 1936 the Squadron Commander and other officers of the Raleigh at a luncheon in a muddy village in the suburbs of Valencia. During the meal, the local “Committee” – referring to the Republican socialistic form of government – “looking like ordinary laborers, called to welcome the party and expressed cordial greetings” and “voted to permit one of the officers to purchase a live turkey”.

Protocol amongst the foreign ships sometimes took unusual turns, e.g. the Senior Naval Officers of the French, British, United States and Italy, operating on the South Coast of Spain:

“* * * agreed to forego passing honors for ships except “attention” on bugle; and that a both boarding calls and official calls (when made) should be in service dress without sword, except before noon on Sunday, when frock coat would be worn. ”

In February of 1937 the RALEIGH visited Naples reporting as follows:

“On arrival the Commander of an Italian Destroyer was assigned to liaison duty and motor car placed at Squadron Commanders disposal. The Assistant U.S. Naval Attache at Rome, Lt. Cmdr. Forrestal * * * rendered valuable assistance.” R18

(Later in World War II U.S. Naval Attache Forrestal would play an important role.)

While in Rome,”* * * all calls, ceremonies and entertainments were planned and carried out with meticulous care”; calls were made on the Italian Undersecretary of Marine, Deputy Chief of Staff and Chief of Staff to the Undersecretary of Marine; luncheons and dinners abounded; tea with the French Naval Attache; evening reception by the Egyptian Minister in honor of the birthday of the King of Egypt; and large afternoon reception attended by several hundred members of the Diplomatic Corps, Italian officials and citizens, American and British friends and residents.

On February 11, 1937 the Squadron Commander visited with Il Duce, Chief of Government. Reporting on this visit he stated:

“Il Duce was cordial in his greeting and talked very agreeably in good English * * *. * * * the audience was a special concession; * * * undoubtedly due to the cordial feeling which he, in company with all Italians, entertains for Americans generally. The privilege of meeting him was deeply appreciated.”

Not all activities on board were serious, e.g. in mid-June the American Ambassador to France, with his young daughter was entertained at a luncheon on board the RALEIGH.

In July, the RALEIGH visited Lisbon where it found government officials very friendly and cordial in character; the Squadron Commander laid a wreath on the Portuguese Monument for World War Dead; a tea was given for the American colony of about 50 persons; and an official luncheon given to the Portuguese Minister of Marine who was a student aviator at Pensacola and “proud of his wings which he still treasures”.

In November of 1937, the Squadron Commander called on a representative of the Sultan of Morocco, Hadj Muhammed Tazi, at his palace in the city; however, the Sultan was unavailable.

On November 18, the CLAXTON visited Tangier, where its

Commanding Officer learned that the British had written off the Spanish Loyalist forces, the American Diplomatic Agent at Tangier, Mr. Blake, quoting Sir Charles Harrington, Governor of Gibraltar, as saying that the Spanish situation was “all over but the shouting.”

On January 19, 1938 the RALEIGH visited Genoa, Italy and the American Colony there gave a dinner dance. The next day the Squadron Commander and several officers were taken on a tour of the White Palace Museum by Italian Prefect of Liguria, attended by over 100 leading local civilian, military and naval officials. The Squadron Commander observed that “This unusual gesture of the Prefect was considered a warm expression of friendship and good feeling toward the visiting Americans. Continuing good will was evidenced by the Mayor of Genoa placing two boxes at the Opera at the disposal of ship’s officers.

Visits to Leghorn and Naples in February of 1938 resulted in more entertainment as well as official calls. In Naples, the Squadron Commander had an audience with the Crown Prince of Italy at his palace in Naples. Later the Crown Prince had a private visit on the RALEIGH, followed by other ceremonies and luncheons. In February the RALEIGH (Q) also visited Tunis, Tunesia.

SHIP SEIZURE, DAMAGE AND REPAIRS

On May 29, 1937 the German ship DEUTSCHLAND was bombed at Iviza by two Spanish government airplanes, resulting in retaliation by the bombardment of Almeria by the ADMIRAL SCHEER and three destroyers on May 31, and culminating with the withdrawal by Italy and Germany from the Non-Intervention Committee and Patrol. Europe was said to be in a:

“high state of tension” and a “great deal of apprehension concerning possible future action by Germany and Italy, as yet undisclosed.”

Officers of the U.S.S. KANE and the DEUTSCHLAND exchanged boarding calls on May 30,1937 at which time KANE’S boarding officers observed that the No. 3 gun was trained at O degrees; saw 23 dead on deck covered with flags; reported 83 injured. Trained nurses were sent by England to assist in caring for the injured.

On January 15, 1938 (R) the RALEIGH was rammed by a Scottish ship off the coast of France. On April 28, 1938 the flag of Admiral Lackey was transferred to the OMAHA (S).

MINING OF SHIPPING LANES AND HARBORS

In March, 1937, bad weather forced the HATFIELD to abandon her plan to visit St. Jean de Luz to obtain information on mines.

In April, still concerned about drifting mines, the Squadron Commander reported that “* * * these mines are drifting off shore and may be encountered in areas normally used by shipping.

U.S.S. MANLEY reported in November of 1937, increased mining activity between Cape San Antonio and Tortosa; with a similar warning by British at Gibraltar.

RELATIONS WITH ALLIES

Apparently, cordial relations existed throughout the Spanish Civil War between U.S. personnel, and those of Britain and France. For example, as early as mid-October 1936 it was reported that the attitude of French officials at Villefranche was one of “marked cordiality”. Monaco Prefet Mouchet was cited as being of great help and whose “cordiality and sincerely are unquestioned”.

Squadron commanders were in constant touch with their British counterparts, as for example reports of German men-at-war engaged in “hovering” off Spanish ports “In conversation with British authorities at Gibraltar, * * * was confirmed”; and the British were “* * * firmly convinced from what they consider reliable authority that support by the Italian Navy to Rebel Navy has been definitely promised * * *; and the * * * the Italians are now patrolling between Cape Bon and Sicily and also in the Greek archipelago against the reported movement of Russian munitions and supply ships * * *.

In April of 1937, at Menton, France, the Squadron Commander and Commanding Officers of all ships “* * * accompanied the Mayor at the ‘Battle of Flowers’. In the evening, all ships participated in the illumination feature of the ‘Fete de Nuit’. Officers attended the Mayor’s Ball and enlisted men were present at a public ball at the Grand Casino.

In July, the RALEIGH visited Oran, Algeria to obtain fuel at low prices, but managed to celebrate the French holiday (July 14) by reviewing French troops on parade. Additionally, the Squadron Commander was motored around the countryside by the U.S. Consular Agent who had “little information of value to offer.”

SUMMARY

Throughout the Spanish Civil War, United States Ships played an important role in protecting U.S. citizens by evacuation, gathering and disseminating information relating to military operations of both the Republicans and the Nationalists.

ADDENDUM

1/ INDIVIDUAL PARTICIPANTS For example, renowned participants in the Spanish Civil War included Dr. Norman Bethune of Canada (introduced the first use of blood transfusions by mobile units at the battle front); Joseph Broz (later known as Marshall Tito, the head of Yugoslavia who organized the Yugoslavic International Brigade fighting on the side of the Loyalists); Robert Capa (photographer attached to the International Brigade – famous for taking the most noted photograph of the Spanish Civil War picturing the “moment of death” as shown in July 17, 1937 Life Magazine); Errol Flynn (reportedly an active fascist supporter); Ernest Hemingway (author of several books on the Spanish Civil War, e.g. For Whom the Bell Tolls); Dolores Ibarruri (famous woman Communist leader fighting for the Loyalists); Oliver Law (as commander of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, became the first American black in history to lead a mostly white unit); Andre Malraux (author of Man’s Hope); Captain Robert Merriman (beloved first commander of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion who died in battle and was the fictionalized hero depicted in Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls; Bruno Mussolini (commanded an Italian air force squadron, was the son of Benito Mussolini, Italian Dictator); George Orwell (fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, noted author of 1984 and Homage to Catalonia; Harold A.R. (Kim) Philby (Britisher recruited by Soviet Intelligence as a mole, acted as a British intelligence agent with Franco’s Nationalists); Wolfram Von Richtofen (Chief of Staff of the German Condor Legion in Spain and cousin of the infamous Red Baron of World War I); Paul Robeson (American opera star who lost his passport for traveling to Spain to support the Loyalists by entertaining troops); Esmond Romilly (fought with the German Thaelmann battalion of the International Brigade, was the cousin of Winston Churchill); James Yates (American black who fought on the Loyalist side with the Thaelmann Division of the International Brigade, author of Mississippi to Madrid).

2/ National Archives of the United States, Annual Reports of the Fleets and Task Forces of the U.S. Navy, 1920-1941; Roll 15, Special Service Squadron July 1921-June 1940; and Squadron 40-T October 1936-October 1939 ; commander’s reports; declassified in 1974. Unless otherwise noted, all references contained herein are to this publication.

3/ National Archives and Records Administration, 1985, #045 National Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library NNRM-93-0l0192-5C, Cruising Reports of U.S. Naval Vessels.